Part 2: Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest: The Past

The desire to resuscitate the suddenly dead is as old as recorded history. Nothing was more terrifying and mysterious as death, particularly in its sudden manifestation.

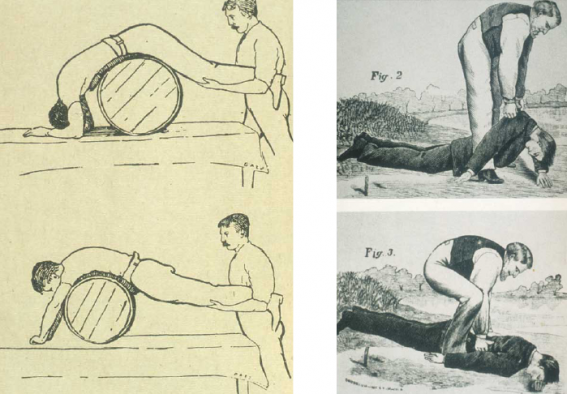

A variety of techniques were proposed for aiding victims of drowning. None were very effective.

Coronary artery disease was not widespread until the 20th century, when for a variety of reasons (lengthening life expectancy, increasing hypertension, more smoking, less exercise, high saturated fat diet) it became and remains the leading underlying cause of sudden death in contemporary society.

Two developments allowed for sudden cardiac arrest to become treatable.

The first was defibrillation, developed in the 1930s, and successfully used on a human in 1947.

The first defibrillator sprang from research into treatment for electrical line workers accidentally electrocuted. It was known that an electrical shock could induce ventricular fibrillation and that a second electrical charge delivered to the heart could stop the fibrillation and restore a normal rhythm. Cardiothoracic surgeons occasionally observed the heart go into fibrillation (felt to be secondary to anesthesia) and the only possible treatment – though seldom successful – was open chest rhythmic compression of the heart.

Dr. Claude Beck.

Dr. Claude Beck, professor of surgery, at Western Reserve University in Cleveland (now known as Case-Western Reserve University) was working on defibrillation devices for the electrical industry. He first used his experimental defibrillator on two patients who fibrillated during surgery in 1941 – both were defibrillated but died within a few hours. But 6 years later, Dr. Beck succeeded.

It was 1947 and the location was the university operating suite. The 19-year-old patient was operated on for a congenital chest deformity and as the chest was being closed blood pressure fell to zero. Beck reopened the chest and observed ventricular fibrillation. He began open chest massage while an assistant retrieved his research defibrillator from his lab. It took 45 minutes until the defibrillator arrived and two shocks to defibrillate the heart. The young man made a full recovery.

The second discovery affording the possibility of resuscitation was CPR.

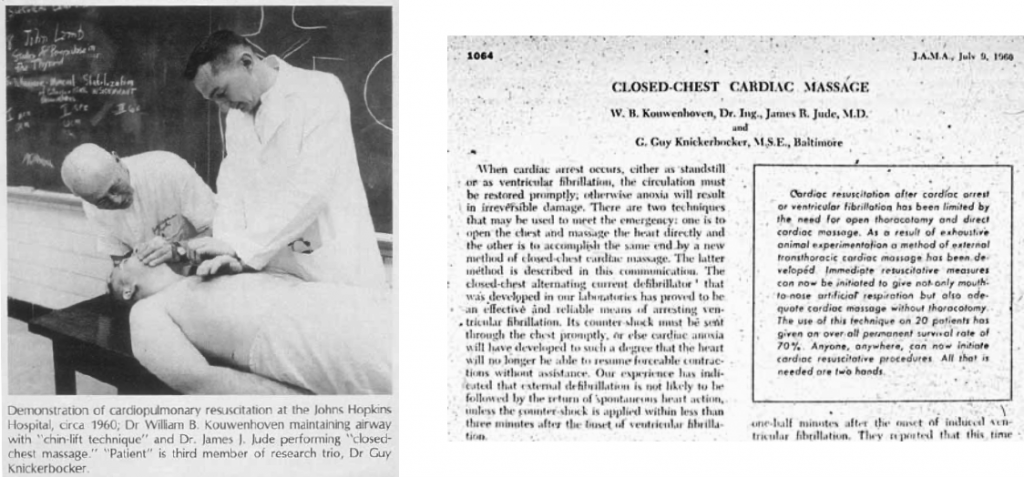

The discovery of CPR in 1960 was accidental. Three researchers (William Kouwenhoven, Guy Knickerbocker, and James Jude) had been working on defibrillation and during a laboratory session with induced VF in a dog, they noticed a blood pressure rise every time they pressed the paddles on the chest. This observation led to the discovery that compression of the chest could reliably cause a pulse and achieve forward blood flow. They refined the technique on dogs and then felt ready to try CPR on hospitalized patients in 1959. The next year in a landmark article in the Journal of the American Medical Association they reported on 20 patients receiving CPR (ages ranged from 2 months to 80 years and all were in VF. The duration of CPR ranged from one minute to 65 minutes. 14 were resuscitated and discharged for a survival rate of 70%.

The discovery of CPR in 1960 was accidental.

It has been 73 years since the first successful defibrillation and 60 years since the discovery of CPR. What was appreciated then is still the bedrock of resuscitation.

CPR keeps the heart alive until definitive therapy provided by defibrillation is delivered. Sure, there have been advances in both procedures and improvements in airway management as well as pharmacological therapy, but the fundamental criticality of CPR and defibrillation remains unchanged.

CPR spread quickly and soon doctors and nurses throughout the nation learned the procedure. In the late 1960s and early 1970s CPR was taught to rescuers, fire fighters, boy scouts, and lifeguards. Both the American Heart Association and American Red Cross promoted training of CPR to the general public, starting in the 1970s.

The trail to emergency medical services (EMS), as we know it today, was blazed in the early 1970s by five cities: Seattle, Miami, Los Angeles, Columbus OH, and Portland, OR. The effort to start out-of-hospital cardiac resuscitative services was catalyzed by a Lancet article describing a mobile intensive care unit in Belfast, Northern Ireland that resuscitated 5 of 10 patients in VF whose cardiac arrest occurred outside the hospital.

These communities and the thousands of communities which followed, used paramedics (specially trained in resuscitation and other life-saving skills) to provide “hospital level” care directly at the scene of a cardiac arrest.

Left: Article from The Lancet in 1967; Right: Dr. Leonard Cobb, founder of Seattle Medic One.

Prior to paramedics, care was provided by rescue personnel, who were trained in CPR but unable to provide defibrillation or medications. (In 1970 formal training and designation as emergency medical technician became the national standard for rescue personnel). Typically, the fire department or private ambulance services responded to cardiac arrests. In smaller towns the ambulance often functioned as a hearse – not inappropriate given the vast majority of unsuccessful resuscitations at the scene.

The Resuscitation Academy

There are opportunities to significantly increase survival from out of hospital cardiac arrest. Implementation of existing standards and training programs for telephone CPR and high-performance CPR will do much to improve survival.